Hilma af Klint: The Secret Paintings at the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Hidden from history, Swedish born artist Hilma af Klint has now emerged into a world that welcomes her mystic thinking, organic form, and pastel colour palette.

Words: Emma-Kate Wilson | Photography: Jenni Karter

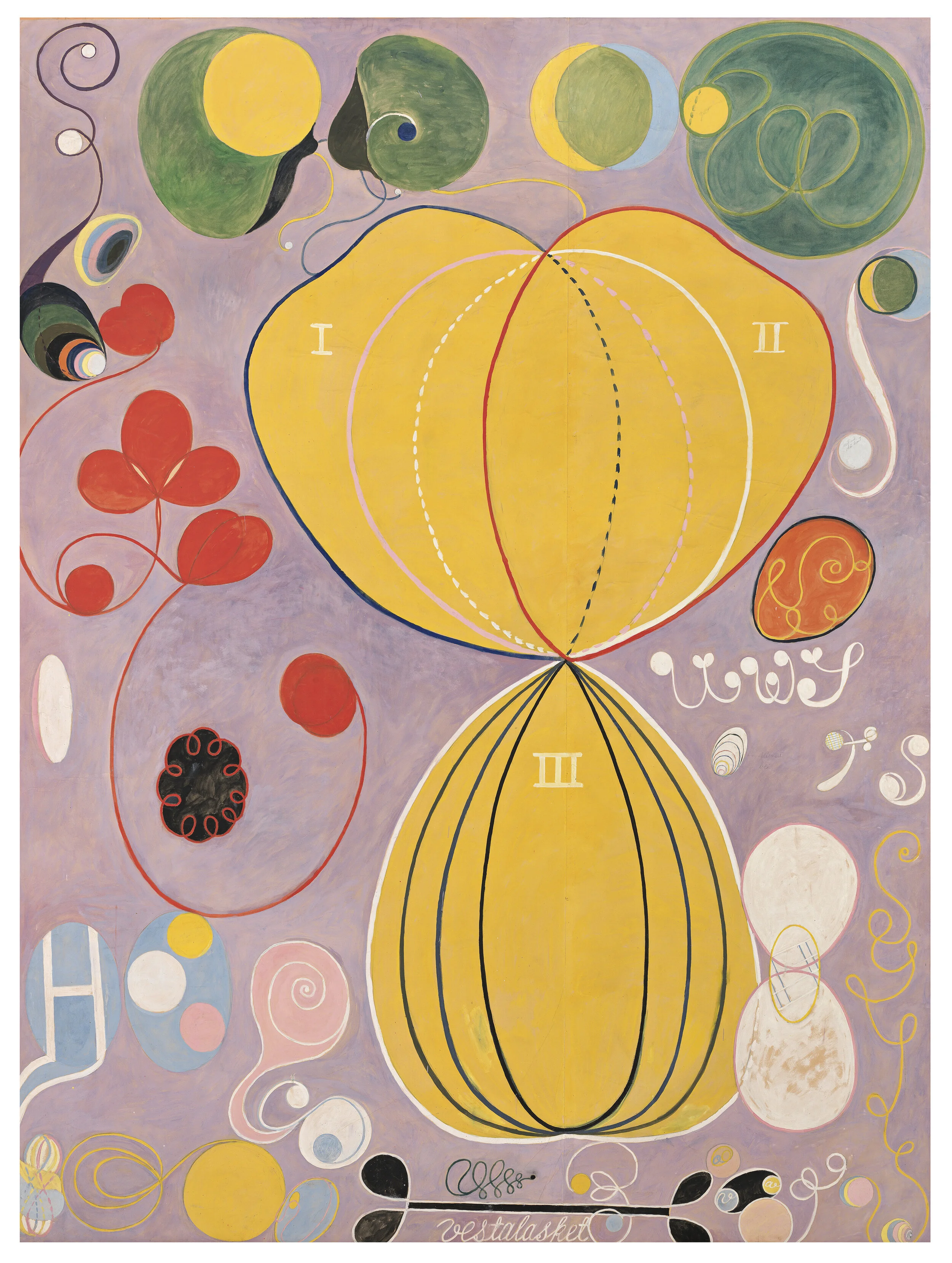

Group IV, The Ten Largest, No 7, ‘Adulthood’, 1907 by Hilma af Klint. Courtesy of Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: The Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

Hilma af Klint at her studio in Hamngatan 5, Stockholm, 1895. Photo courtesy of Hilma af Klint Foundation, Stockholm.

Swedish artist Hilma af Klint knew she was working ahead of her time, so much so that when she died, she asked for her paintings to be hidden from the public for at least 20 years. Engaged with spiritualism and interested in the new developments in science and knowledge of the natural world, af Klint engaged the higher spirits to inspire her artworks.

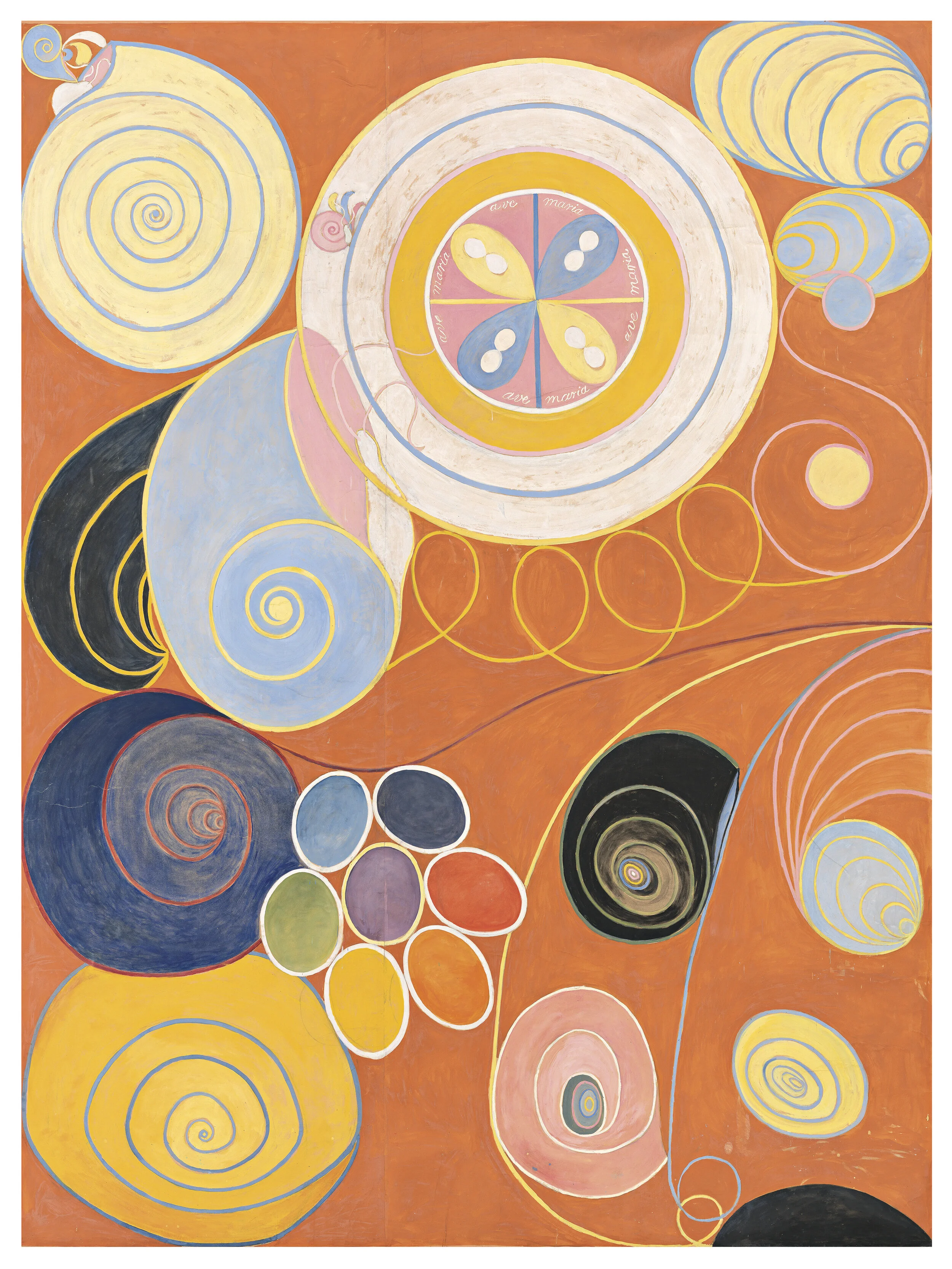

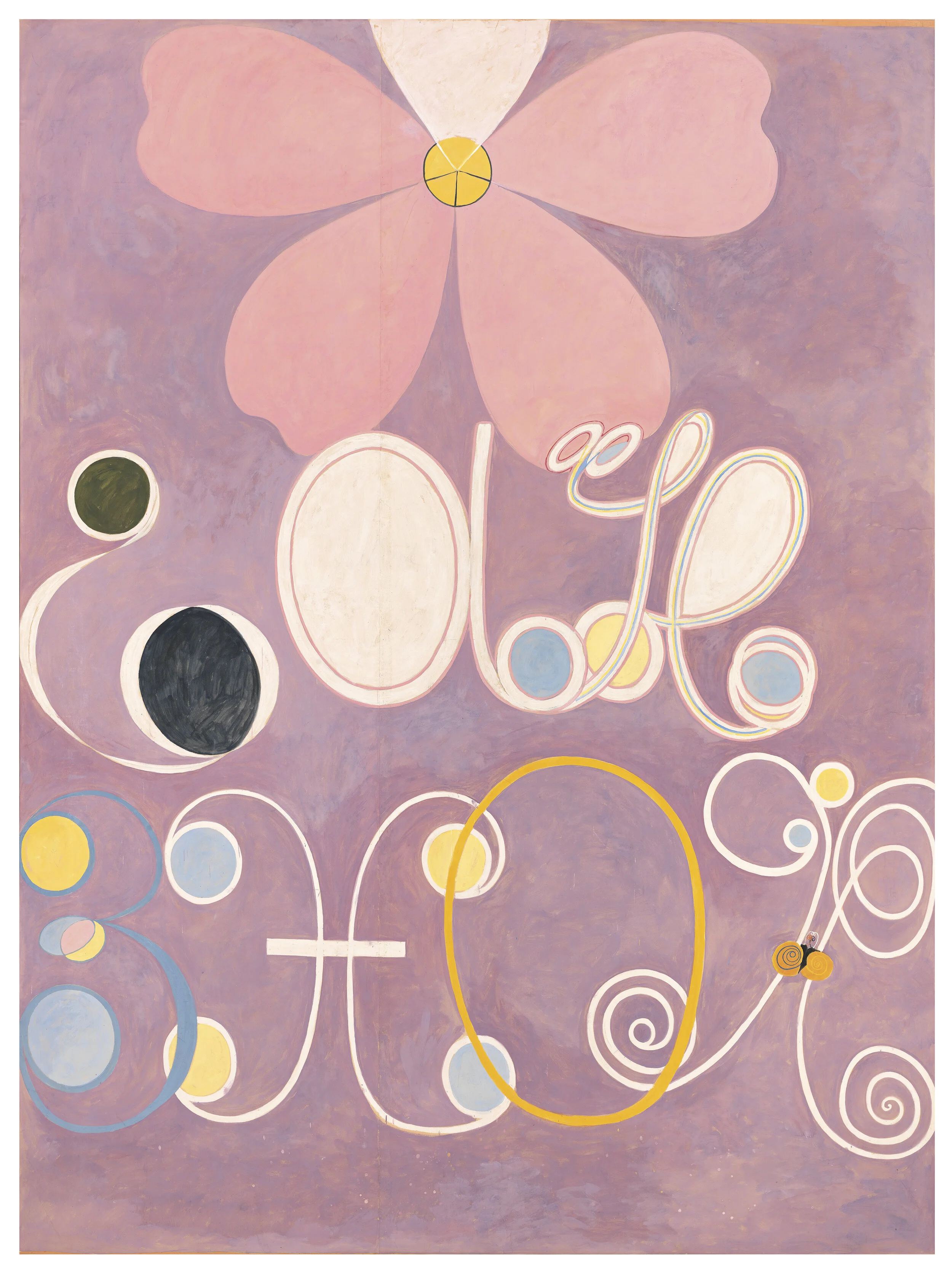

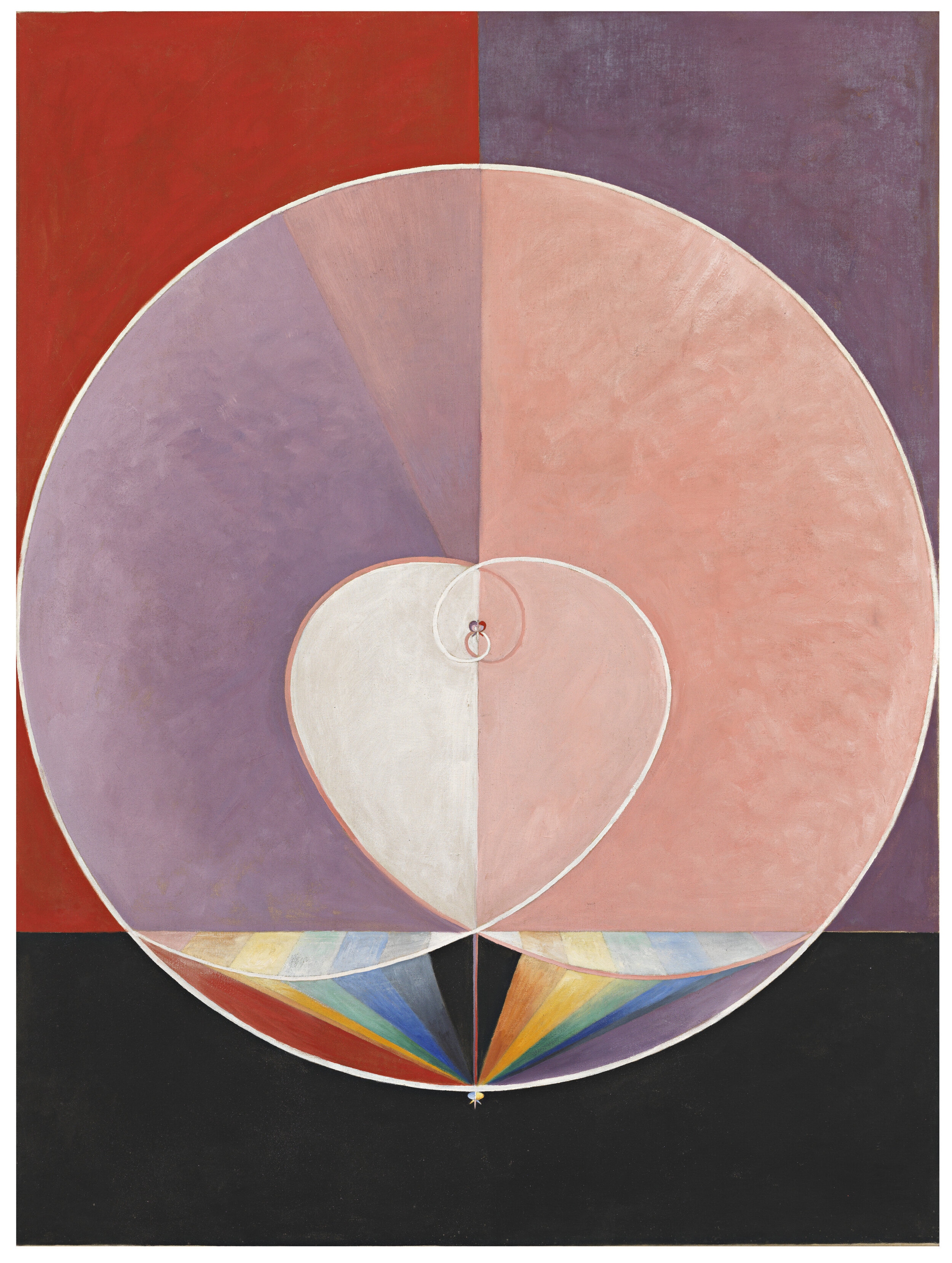

The result varies in palette hues, uncannily as though picked from Instagram’s interior design hashtags. Bubble-gum pink, lavender, and peach complement burnt orange, dusty blues and bright yellows in the larger-than-life paintings, The Ten Largest (1907). These works are part of af Klint’s decade long project The Paintings for the Temple (1906 - 1915), which ends with the Altarpieces in 1915, three paintings showing an intense spiritual engagement comprising of circles and triangles in graduating colours of a more primary nature.

Af Klint’s spiritualist oeuvre as we know it developed from 1906, following her radical break from the naturalistic conventions she had learned while training at Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, from which she graduated with honours in 1887. Her early works encompassed landscapes and botanical paintings, which can be seen alongside the epic paintings in the Art Gallery of NSW exhibition, Hilma af Klint: The Secret Paintings.

Independent curator Sue Cramer curated the exhibition, collaborating with the Art Gallery of NSW’s Nicholas Chambers. She wanted to reveal how af Klint’s style had progressed from the profound influence from nature and the occult while alluding to the secrecy of her practice. Alongside the intricate spirals, geometric flowers, and free-flowing form of The Paintings for the Temple, Cramer included 42 watercolours that (mostly) have yet to be seen across the world.

View of The Ten Larges on display at the Art Gallery of New South Wales as part of Hilma af Klint: The Secret Paintings. Photo: Jenni Carter.

“I am fascinated by how af Klint was working for the future, her work feels incredibly relevant to contemporary artists and audiences.”

Group IV, The Ten Largest, No 2, ‘Childhood’. Courtesy of Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: The Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

Group IV, The Ten Largest, No 3, ‘Youth’ by Hilma af Klint. Courtesy of Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: The Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

‘I was keen to focus on her paintings for the temple as being like the central body of work, and at the same time, give a sense of the early years of her life,’ says Cramer. ‘I wanted at the end of the exhibition to include some of the notebooks and drawings that came after 1915. They are the culmination of her life’s work; we move through into a period where she returns to a study of nature and looks very closely at plants.’

Her (now) iconic works unfolded after af Klint delved deep into spiritualism, Rosicrucianism and Theosophy. In 1896, she founded the spiritual group ‘The Five’ with four other like-minded women. Together they ‘studied esoteric texts, conducted séances, exercised automatic writing and mediumistic drawing. In 1917, af Klint claimed the spirits stopped guiding her process and instead she became an “interpreter”, gaining subjective control over her work.

What is most incredible about the works is the fact that they pre-date the ‘official’ timeline of Western abstract art — before the likes of Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian. ‘The mark-making is very contemporary,’ Cramer continues. ‘It’s unlike anything that was being done at the time, and how bravely she broke away from the conventions of her academic training at the Royal Academy.’

Only in 2013 was af Klint’s art seen in a museum retrospective at Stockholm’s Moderna Museet before being catapulted to the global contemporary art discourse with the ‘sensation’ show at Guggenheim in New York 2019. As Cramer reflects, ‘the work just does have this extraordinary presence in the now—it speaks to contemporary audiences so vividly.’

Group IV, The Ten Largest, No 5, ‘Adulthood’, 1907 by Hilma af Klint. Courtesy of Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: The Moderna Museet, Stockholm

Group IX/UW, ‘The Dove’, No 2, 1915 by Hilma af Klint. Courtesy of Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: The Moderna Museet, Stockholm